All About the Mountain Bluebird found in Southern Alberta

Mountain Bluebird

Sialia currucoides

Thrushes

Family: Turdidae

Order: Passeriformes

Class: Aves

Phylum: Chordata

Kingdom: Animalia

Domain: Eukaryote

Also known as:

Merlebleu azuré

(French)pi'ksíí

(Blackfoot)Azulejo Claro

(Spanish)

Similar species:

Western Bluebird - Sialia mexicana

Eastern Bluebird - Sialia sialis

Identification

The Mountain Bluebird is a medium-sized bird weighing about 30 grams with a length from 16–20 cm. They have light underbellies and black eyes. Adult males have thin bills and are bright turquoise-blue and somewhat lighter underneath. Adult females have duller blue wings and tail, grey breast, grey crown, throat and back.

Primary Colours

Males:

Cerulean/Turquoise-blueFemales:

Grayish brown

Mountain Bluebird - Male

“A large bluebird with no distinct patches of orange or red on either sex. Adults are sexually dimorphic in plumage color but not visibly different in size. The upperparts of adult males are a rich cerulean-blue, although the wing tips are dusky. The throat and upper chest are a distinct cerulean-blue fading to a pale blue moving down the breast to the white lower belly.”

Description © Michael Andersen, Wyoming United States, June 2011.

Photo by Ken Orich

Mountain Bluebird - Female

“Adult females are grayish brown on the head and upper back, sometimes tinged a light cerulean-blue. The rump stands out as a patch of light blue. The color of the throat, chest and upper belly are pale grayish brown, with the chin area lighter than the throat and chest. The lower belly and undertail coverts are white. The scapulars, primary, and tail feathers are a light cerulean-blue.”

Description © Brian Sullivan, California, United States, February 2017.

Photo by Ken Orich

The Sibley Field Guide to Birds of Western North America (2003), by David Allen Sibley, provides the follow description for Mountain Bluebirds on page 342:

A Guide to North American Species Bird Feathers (2010), by David S. Scott & Casey McFarland, provides the following feather identification on page 273:

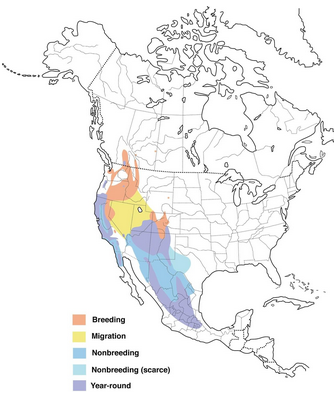

Citizen Science data provided to eBird and Birds of North America by The Cornell Lab of Ornithology provides a fairly detailed range and relative abundance for Mountain Bluebirds.

Range map of the Mountain Bluebird in Southern Alberta from eBird.org. Help keep this map up to date by submitting your sightings to eBird.org!

Habitat & Behaviour

Fencepost near open woodlands is ideal for Mountain Bluebird nest box placement

The Mountain Bluebird’s preferred habitat is sparsely treed grasslands or open woodlands. They require cavities for nesting.

During winter, Mountain Bluebirds travel in flocks, often with Western Bluebirds and Sparrows, and feed on insects and small fruit, such as mistletoe, hackberry, and currants.

They typically begin to move north in March, but often arrive in northern latitudes when snow still blankets much of the ground and temperatures still dip below -20°C. These hardy birds can usually withstand short spells of cold and stormy weather; however, during prolonged severe conditions they may freeze or starve to death. Mountain Bluebirds sometimes migrate alone but more often travel in flocks of up to 50 birds (rarely up to 200). They travel during the day at a leisurely pace, stopping frequently to feed.

They can sometimes be seen strung like brilliant blue jewels along a barbed wire fence, scanning bare patches of ground for weed seeds and dead insects. Highly aggressive birds, they usually sit at least a metre apart. There is a continual flashing of blue, as first one and then another leaves its perch momentarily to pick up a tasty morsel.

Diet & Feeding

Like other thrushes, Mountain Bluebirds are ground-feeders and eat mostly insects, spiders, grasshoppers, and flies.

Where elevated perches are not readily available, particularly near nest sites, the Mountain Bluebird will obtain most of its food by hovering in the air a metre or more above the ground in a hawk-like manner, as it searches the earth below for food. Other members of the thrush family do not use this hovering technique.

Sounds & Calls

Mountain Bluebirds have distinct song types:

a warble vocalized by males at first light of day

a soft burry chortle or whistle between the male and female

when disturbed they will chik, chak, and clack their beaks

Nesting & Breeding

Before the tail end of the migration has passed through, resident Mountain Bluebirds have fanned out over areas with suitable nesting habitat. Sparsely treed grasslands, wooded ravines and valleys, badlands, and mountains all meet the nesting requirements of Mountain Bluebirds, but they tend to avoid treeless plains.

The males often arrive first, and waste little time in searching out suitable nesting sites: woodpecker excavations and decayed cavities in trees are used where available. In built-up areas, they move into machinery, nooks and crannies in buildings, fence-posts, and utility poles. Recently, the birdhouse has become an important nesting site.

Once a male has established territory early in the season he will try to attract a passing mate through beautiful singing. Males may engage in flight displays, wing-wave displays, entering/exiting cavity repeatedly. He may offer bits of nesting material and food. He may also preen his potential mate in an effort to gain her affection. His exuberant display may last, off and on, for hours or even days,

Females seem most interested in the territory - inspecting the nest box and surrounding territory to ensure it meets her expectations. Her acceptance of the nest site is usually a sure-bet if she enters the nest site with nesting material.

After a nest site is agreed upon, both birds defend the immediate area. They build the nest of dry grass stems and finer plant material, while continuously watching and guarding the new site against intruders. This process may take any where from two days to more than a week.

Soon after completing the nest, the female lays one egg each day until the clutch, usually with four to six eggs, is complete. Occasionally there are up to eight eggs in a clutch.

Both parents will feed the newly fledged young. Males may takeover this duty if the female starts another clutch. It has been documented that young from the first brood may help feed siblings from the second brood. There have been cases where three broods are recorded in a season in eastern Alberta.

Banding research suggests that Mountain Bluebirds do not retain the same mate for more than one season.

Learn more at: NestWatch | Mountain Bluebird

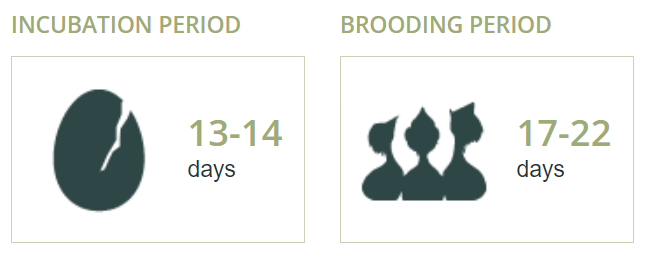

Mountain Bluebird Life Cycle

Nest building - 1 to 6 days

Egg laying - 5 to 7 days

Incubation - 12 to 15 days

Nestling - 17 to 22 days

Fledgling - 21 to 28 days

Expected life span - 4 to 6 years, oldest on record is 10 years, 5 months

Want to take a closer look inside the nest box?

Check out this great video about Mountain Bluebirds by MBTCS Trail Monitor Rick Andrews:

Three Species of Bluebirds in North America

Range Maps from The Cornell Lab’s All About Birds

Click map to go to their site for more details:

Mountain Bluebird - Sialia currucoides - Male

Mountain Bluebirds inhabit western North America. Its breeding range extends from the Yukon Territory, south through British Columbia east of the Coast Range. It breeds as far east as eastern Manitoba. The Mountain Bluebird is the most migratory bluebird species, although many individuals simply move locally to lower elevations.

Western Bluebird - Sialia mexicana - Male

Western Bluebirds are characterized by a blue throat and rusty upper back and breast, shares some of the Mountain Bluebird’s range in southwestern Canada. It occupies southern British Columbia through southern California into central Mexico and northward up through New Mexico to western Montana. It is scarcer than the Mountain Bluebird, except west of the coast ranges.

Eastern Bluebird - Sialia sialis - Male

Eastern Bluebirds with deep sky-blue back and crown and chestnut-red throat and breast, are found from southern Saskatchewan to Nova Scotia, along the east coast to Florida, and around the Gulf of Mexico to western Texas.

Conservation History of Mountain Bluebirds

Bluebirds probably were never common, as they were limited by their nesting requirements. However, in the 1800s as colonists spread out across North America and cleared heavily wooded areas, bluebird habitat increased. The settlers also controlled prairie fires, which allowed more trees to mature and develop nesting cavities.

In the early 1900s, the bluebird’s future looked promising. But this era of good fortune was short-lived: more settlers arrived, land became more valuable, and many thousands of hectares of bluebird habitat were completely denuded of trees annually for farming. Also, Europeans brought with them intruders—starlings and House Sparrows—which had little difficulty in evicting the bluebirds from the few remaining nest sites.

Bluebird numbers continued to decline until some naturalists felt the bluebird was doomed to extinction. Fortunately, bird lovers across North America began in the 1920s to build bluebird nest boxes in an attempt to reverse the decline. This conservation effort really became popular during the 1950s and 1960s. The results have been encouraging.

Today, humans still compete for habitat with bluebirds. Forestry practices that remove dead trees and snags reduce the available nesting cavities for bluebirds. Some people have helped to offset this loss by creating trails of bluebird nest boxes. Unfortunately, sometimes other people vandalize nest boxes and destroy their contents.

Although bluebirds tend to arrive early enough in spring to get first choice of the available nest boxes, they must sometimes compete for them with Tree Swallows, House Wrens, Chickadees, House Sparrows, and European Starlings. Starlings can be excluded from the competition by an entrance hole no larger than 3.8 cm (1 9/16”) in diameter. In addition, each of the three bluebird species competes with the others for boxes, where ranges overlap.

Once installed, bluebirds are well able to defend boxes that are properly designed and placed to their liking. However, where House Sparrows are abundant they may enter a bluebird box and go so far as to kill young and adult bluebirds. Although it is too large to enter their nest boxes, the main avian predator of the bluebird is the American Kestrel, a small hawk. Domestic cats and raccoons are formidable predators of young and incubating female bluebirds. Deer mice and chipmunks can also be problems. Smooth metal posts will often prevent animals from climbing up to nest boxes.

A parasitic blowfly Apaulina Stalia takes its toll of bluebirds in some areas, although it is not thought to reduce population size. The fly lays its eggs in the bird’s nest, and the larvae attach themselves to the young birds and may kill them by sucking their blood. This parasite can be controlled by dusting nest boxes with diatomaceous earth.

Trail Monitors are citizen scientists who support habitat for cavity-nesting birds.

As a result of bluebird banding programs, we now know that some bluebirds nest when they are one year old. The average age for a Mountain Bluebird is four to six years (oldest is 10 years 5 months), and an Eastern Bluebird is approximately eight years. Banding has also shown that successful breeders often return to the same area or nest site each year.

Contrary to popular belief, very few young bluebirds return to nest in the area in which they were raised. In one study area, less than one percent of the young fledged were found nesting in that area in subsequent years. Probably, many do not survive to breed, and survivors disperse to new areas. The erection of thousands of birdhouses by concerned individuals and organizations has been responsible for preventing further depletion of bluebird numbers and in many areas has increased populations.

The location of a bluebird nest box is important. Nest boxes should be placed in semi-open areas such as pastures, fields, and rural roadsides. A fence post in a clearing with scattered trees about 20 m away is probably a good location. Nest boxes in urban areas or near farm buildings are usually occupied by house sparrows.

The nest box should be placed on a post 1 m or more above the ground. The entrance hole should be opposite to the prevailing winds. So, if your wind is generally from the southwest then the entrance should be placed to the northeast.

A “Bluebird Trail” consists of several nest boxes spaced 200 m or more apart and in a manner convenient for inspection on foot or by car, to record nesting success, band young birds, and clean out boxes in the fall. Regular inspections also allow the nest caretaker to remove nests of House Sparrows and other intruders. Some trails may be only a kilometre long, while the longest runs several hundred kilometres from Winnipeg, Manitoba, to North Battleford, Saskatchewan, with hundreds of kilometres of branch lines leading off from the main trail.

Learn more about Mountain Bluebirds

Thank you to all Bluebird enthusiasts for increasing our collective knowledge about these wonderful animals. Below is a select bibliography for this website.

These resources will help you to take your study of Mountain Bluebirds (Sialia currucoides) to the next level.

Please let us know about other great resources we can add to this page!

Online Resources

Print Resources

Bent, A. C. 1964. Life histories of North American thrushes, kinglets, and their allies. Dover Publications Inc., New York.

Fisher, Chris, and Acorn, John. 1998. Birds of Alberta. Lone Pine Publishing, Edmonton.

Godfrey, W. E. 1986. The birds of Canada. Revised edition. National Museums of Canada, Ottawa.

Johnson, L. S. and R. D. Dawson. 2019. Mountain Bluebird (Sialia currucoides), version 2.0. In The Birds of North America (P. G. Rodewald, Editor). Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Ithaca, NY, USA. https://doi.org/10.2173/bna.moublu.02

Pearman, Myrna. 2009. Children’s Bluebird Activity Booklet. Mountain Bluebird Trails Inc., Ronan.

Pearman, Myrna. 2002. Mountain Bluebird Trail Monitoring Guide. Red Deer River Naturalists, Red Deer.

Peterson, R.T. 1961. A field guide to western birds. Second edition. Houghton Mifflin Inc., Boston.

Power, H.W., and M.P. Lombardo. 1996. Mountain Bluebird, Sialia currucoides. In Birds of North America, no. 222. A. Poole and F. Gill, editors. Academy of Natural Sciences, Phildelphia, and American Ornithological Union, Washington, D.C.

Scott, David S., and McFarland, Casey. 2010. A Guide to North American Species Bird Feathers. First edition. Stackpole Books, Mechanicsburg.

Sibley, David Allen. 2003. The Sibley Field Guide to Birds of Western North America. First edition. Andrew Stewart Publishing.

Terres, John K., editor. 1980. The Audubon Society Encyclopedia of North American Birds. Alfred A. Knopf, New York.